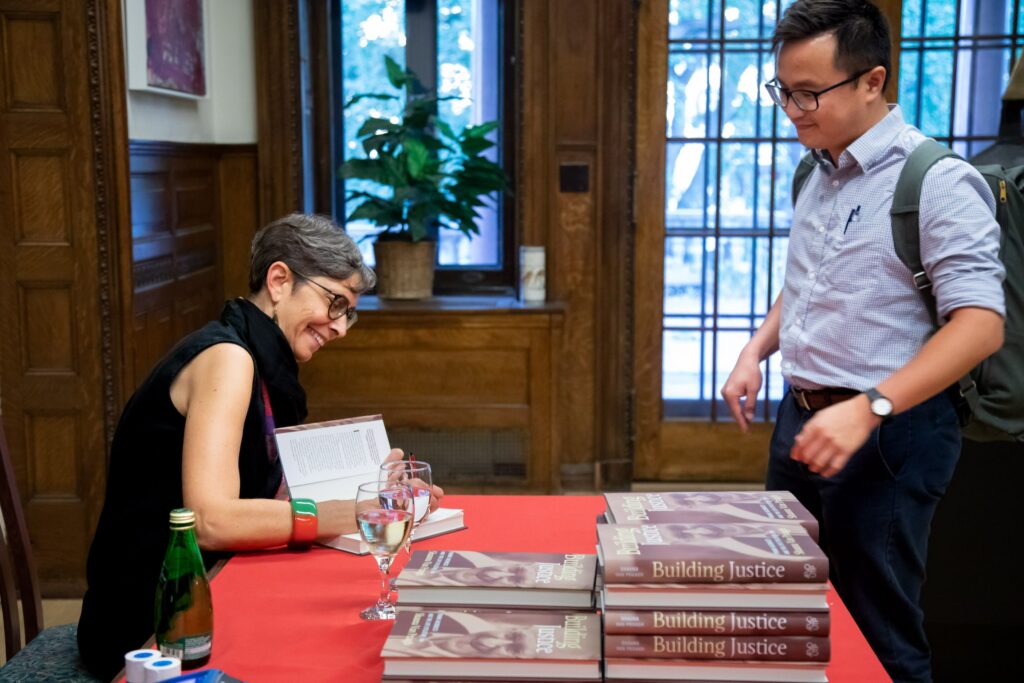

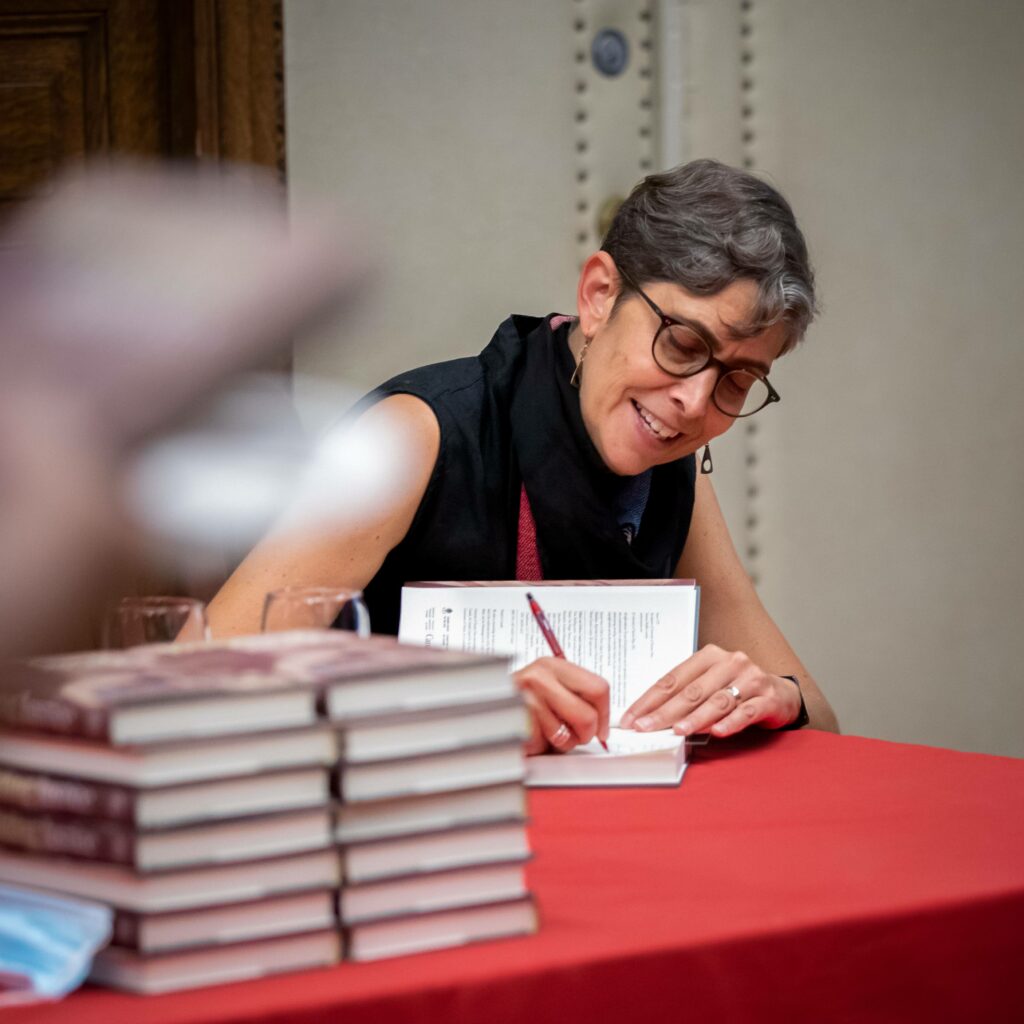

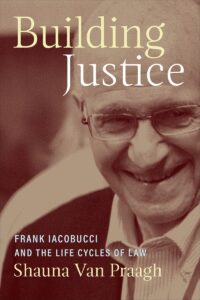

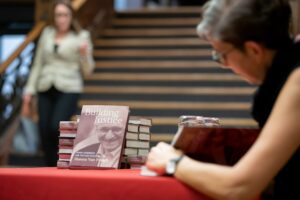

Using this story as a blueprint for her newly published work, Building Justice: Frank Iacobucci and the Life Cycles of Law, Professor Shauna Van Praagh paints a picture by collage of the life of the Honourable Frank Iacobucci and, more broadly, of the possibilities of engaged citizenship through law. Divided into three parts – “Cutting Stone: Welcome to Law”, “$5 a Day: Lawyering in the World”, and “Building a Cathedral: Called to Action” – the book traces the path of this child of Italian immigrants who went to law school despite being told he had “the wrong name” to do so. Frank Iacobucci’s multifaceted contributions to Canadian law and society include serving as university leader, public servant, Supreme Court Justice, and negotiator of a broad settlement scheme for residential school survivors. His trajectory sheds inspiring light on what prepares us for a legal education, what we can do with a law degree in hand, and what it means to serve as a jurist.

In the book, you share the story of how you first met Frank Iacobucci – can you tell us about this encounter and your subsequent relationship with him?

Frank Iacobucci was never my teacher, my boss or my colleague; instead, he was an informal mentor – the person who suggested to me that I study law. I first met him when he was a university administrator and I was student president of my undergraduate college. As he sat down after addressing the first year class, he turned to me and asked “Was I OK?”. Many years after reassuring him that indeed he had done a good job, I came up with the idea of writing a book focused on his trajectory and its insights for legal education and the practice of law. As someone who went to law school specifically on Iacobucci’s recommendation, I can say – as I do in my conclusion – that “in an important way, he played a central role in literally shaping my own world.”

As you describe in the preface, Building Justice proceeds by “narrative collage,” weaving together stories in Iacobucci’s own voice and others from individuals who crossed paths with him. Why did you choose this approach, rather than follow the more linear structure one might expect for a biographical work?

I wanted to emphasize the ways in which our impact in the world is marked not so much by achievements but by relationships. At every stage in Frank Iacobucci’s life in law, there are people who supported him, worked with him, learned from him, and were inspired by him. The structure of the book invites them to be heard and included in a way that reinforces the importance of teaching and teamwork in all of our lives. I also wanted to share the responsibility of asking questions, offering comments, and reflecting on the impact of Iacobucci’s contributions and on the responsibilities that accompanied each of his roles. Finally, I wanted to challenge readers to think about their own journeys, their own justice-building projects, and the ways in which their paths intertwine with those of others.

“Serial public servant, scholar, mentor, judge, and family man. The story of Frank Iacobucci is moving and inspiring, filled with vitality and wit. Shauna Van Praagh writes with style and blazing creativity. We learn about the protagonist of course, but much else as well: how law can help you figure out how to live; the role of narrative in life and law; how to address some of the biggest issues in Canadian society. Justice Iacobucci may be right that there is nothing magical about courts but there is in this extraordinary book.”

– Stephen J. Toope, OC, FRSC, BCL’83, LLB’83, LLD’17

Dean of Law, McGill University (1994-1999), Vice-Chancellor, University of Cambridge (2017-2022)

Some might be surprised to find out that Iacobucci’s 13 years on the Supreme Court are recounted in the “$5 a day – Lawyering in the World” part of the book, rather than in “Building a Cathedral.” Could you tell us a bit about this authorial decision?

“I don’t really see anything omnipotent or magical about courts.” This quote from Frank Iacobucci both introduces and concludes the section focused on his contributions as Supreme Court Justice. From the very start of this book project, I was determined to avoid the easy trap of a judicial biography, in which the significance and power associated with sitting on the highest court reinforce the notion that this is the (usually unattained) pinnacle of a jurist’s career. Of course, the book devotes much space and attention to Iacobucci’s judicial “signature”, but I insist throughout that even Supreme Court judgments form part of never-ending conversations. The people who hand them down may illustrate the pursuit of justice, but all jurists share that pursuit whatever they do for “$5 a day”. It is through Iacobucci’s support for the young people who clerked for him that the Court does end up in the “building a cathedral” part of the book, alongside his contributions to the ongoing project of reconciliation between Indigenous and non-Indigenous Canadians.

The book is dedicated to your students – what do you hope they will take away from reading this work?

As I head into my 30th year at McGill, it is probably no surprise that my book examines and underscores the intergenerational character of the teaching and learning of law. The reference to “life cycles” in the title captures the never-ending and never-fixed feel of engagement in law, while “building justice” serves not only a description of the book’s protagonist but as an invitation to participate in an ongoing and shared practice. Many of my students will find parts of this book very familiar as they read about customary standards of care, the complexities of a test for equality, the contours of freedom of expression, the collective dimensions of identity, or the co-existing and intersecting responses to residential school survivors. I hope my students – past, present and future – will read and share the book, think about their own legal education and how they keep learning, and reflect on the ways in which they do or will teach others around them. I trust they will be reminded of the transformative potential and responsibility that come with lawyering. And of course I hope the book acts as an invitation to keep in touch!

“As a law professor, I support future jurists as they learn how to ask hard questions, grapple with principles, situate sources of law in social context, and appreciate the impact of rules and decisions on real people. It is my job to support them as they connect the before, during and after of their formal legal education. It is my job to encourage them to find ways to build a cathedral.”

– Professor Shauna Van Praagh, epilogue of “Building Justice”

“Building Justice: Frank Iacobucci and the Life Cycles of Law” by Professor Shauna Van Praagh is available now at the University of Toronto Press.