John Hobbins traces the history of university-based legal education in Canada—and its origin right here at McGill’s Faculty of Law.

By Bridget Wayland

|

John Hobbins knows a lot about the history of this Faculty, and on February 10, our Librarian Emeritus served up a small taste to an eager crowd.

Law professors, staff and students were among the 45 people who gathered in the Common Room and later, the Moot Court, to hear Hobbins’ wry but enthusiastic lecture on “McGill’s Faculty of Law and the Inception of University-based Legal Education in Canada.”

John Hobbins (BA’66, MLS’68), who retired in 2009 as Head Librarian of the Nahum Gelber Law Library, drew on his original research into the history of McGill’s Faculty of Law to deliver a definitive account of its origins as the first university-based Faculty of Law in Canada.

He took evident delight in communicating outrageous quotations by Lord Elgin (the Governor General), Earl Grey (the Colonial Secretary), then-Principal John Bethune and other key players of the day, as well as the labyrinthine regulations going back to 1821 when the Charter of McGill College was created.

In 1843, once McGill’s Statutes were established, the Faculty of Arts had its grand opening and the powers-that-be clearly stated the Faculty of Law would begin operations as soon as a Professor in Law could be appointed.

Today, it’s generally accepted that the Faculty was born when William Badgley, a prominent lawyer and politician, became our first law professor but, according to Hobbins, pinpointing the exact year is a tricky business. “I went through all the minutes of the Board of Governors and other primary sources,” he said, “and I think that all the scholars are wrong on this issue.”

Did the Faculty exist in 1848? Not officially, it seems. “The 1843 Statutes needed to be changed by the monarch to allow for a functional BCL program, and Badgley himself could not be appointed Professor until the 1821 Charter was amended,” Hobbins said. “The College had the power to award degrees to Badgley’s de facti students, but could not yet claim a de jure Faculty of Law.”

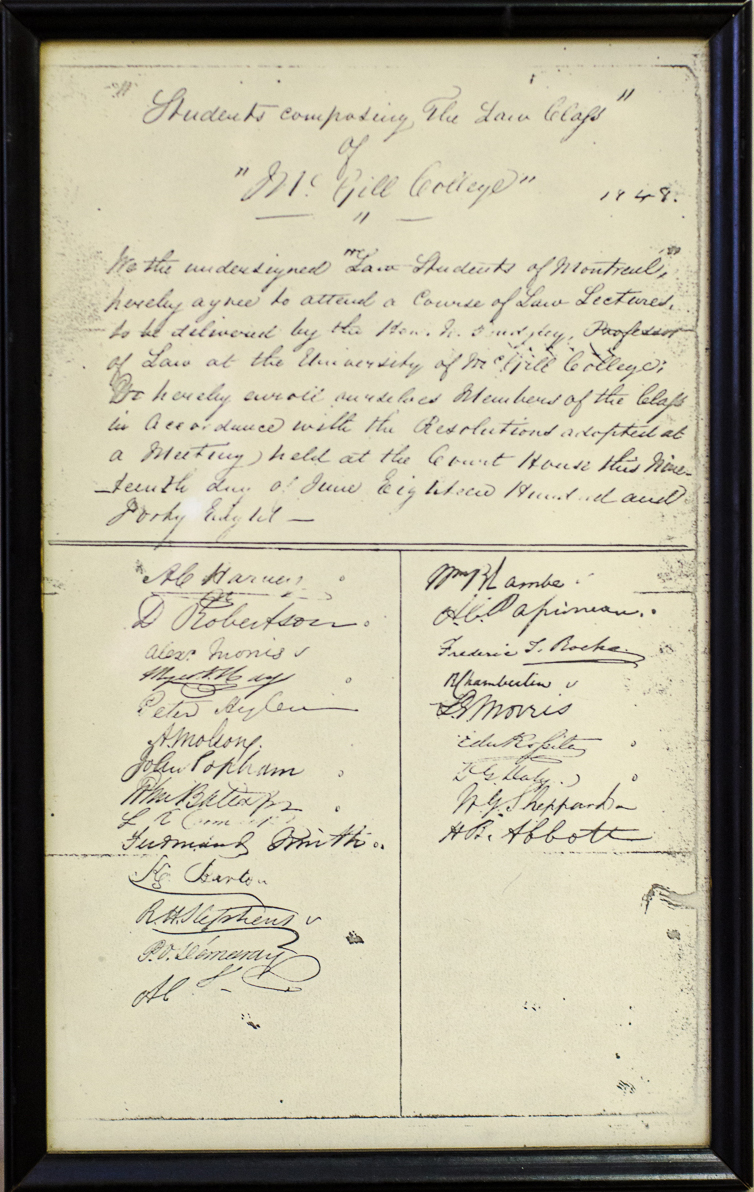

Some credit for creating the Faculty of Law is actually due to a group of twenty-two determined young men, led by one Alexander Morris, who declared themselves the “Law Class of McGill College” in June of 1848. They all signed an undertaking to attend Badgley’s classes, a copy of which hangs outside the Dean’s Office today. Prime among their demands was that McGill should reduce the Classics prerequisite to a mere three terms of residency in the Faculty of Arts, from the full two full years as stipulated in the Statutes.

“These young men had no standing officially,” he said, but their actions made it clear to the College that many students would register for a law degree if the rules were loosened up somewhat. In fact, “the registration of these so-called ‘Resolvers’ would triple the size of the College,” said Hobbins, “as there were only six students resident in Arts at the time. Had it not been for the Law students, it is questionable whether McGill’s Faculty of Arts would have been a sustainable entity at all.”

In 1849, Morris was the first of the bunch to receive his B.A., after a very brief tenure in house at the Faculty of Arts which he used as a stepping stone to begin studying law under Badgley. It was not until 1850 that McGill awarded its first BCL degrees, to six of the Resolvers. At that time, the Faculty of Law still had no official professors, let alone a Dean. “In the Fall of 1853,” Hobbins says, “Badgley was finally promoted from Lecturer to Professor, and made the first Dean of the Faculty of Law.” But it was not until the following year, 1854, that the Faculty awarded its first degrees.

In contrast, “there was no university-based legal education in Ontario until the late 1950s,” said Hobbins, even though Upper Canada had established the first Law Society in 1797. “It was easier, and more practical, to get a degree by articling than by university study,” he said, despite the fact that this legal training was sometimes “a bit iffy.”

Be that as it may, McGill clearly paved the way for legal education in this country. Its precise beginnings may be hard to pinpoint but, as Hobbins can attest, McGill’s legal education program has set the standard for the law profession in Canada for roundabout 160 years.

History at McGill

|

[ JUMP TO THE CURRENT EDITION OF FOCUS ONLINE ]