Claire Kirkland graduated from the Faculty of Law in 1950 and not only went on to become a lawyer, judge and politician but also blazed a trail for women in the halls of power everywhere. Her funeral in Montreal in April was the first ‘National funeral’ for a woman in Quebec.

Focus online presents a 1998 profile of this formidable woman (originally published in the McGill News):

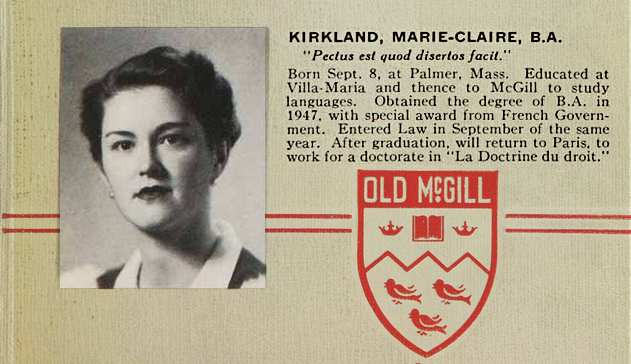

You can be forgiven for some measure of confusion. McGill’s latest honorary degree recipient began her life as Marie-Claire Kirkland, then became Marie Claire Kirkland Casgrain upon marriage. When she ran for the Quebec legislature in 1961, the electoral officer refused to allow her double-barrelled family name on the ballot. So she dropped Marie and substituted her maiden name as her middle name. And nine years ago, she became Marie Claire Kirkland Strover when she married Wyndham Strover, BCL’50. (She was divorced; he, a widower.)

But whatever name one knows her by, Marie-Claire Kirkland, BA’47, BCL’50, LLD’97, can claim a firm place in Canadian history. The first woman to plead before the Quebec private bills committee (headed by Maurice Duplessis), the first woman in the Quebec assembly, the first woman cabinet minister and first woman acting premier of the province. She exemplifies the feminist label “trailblazer.”

As the only child of Dr. Charles Kirkland (who represented the riding of Jacques Cartier in the Quebec legislature) and his homemaker wife, Rose Demers, she recalls being urged to become self-sufficient. “In those days, my father did house calls, and he saw how some women lived, often treated like slaves, just there to bear children.

“My father was a feminist. He’d say, ‘There should be a woman in Parliament — but it would be too hard on her.’ ” Dr. Kirkland introduced Marie-Claire to public life by taking her to political meetings and insisting she study law. “In those days we used to listen to our parents,” she says. “My parents said if I studied law I would be better able to protect myself.”

She came to McGill’s Faculty of Law and found the Quebec Civil Code an affront to women. While single women could give legal value to a document, married women needed their husband’s signature. “Seeing this revolted me,” she said during an interview at her Ile-Bizard home near the west end of the Island of Montreal. When her father died in 1961, Kirkland, then a lawyer, won his riding as a Liberal under Premier Jean Lesage. As the first (and only) woman member, the first issue was whether she’d wear a hat to the National Assembly. She refused to “wear a hat to work”, and the rule fell by the wayside.

Kirkland says she didn’t feel a lot of pressure because people had low expectations. She was clearly the “woman representative.” “When my Liberal Party colleagues received inquiries from women constituents, they directed them to me,” Kirkland recalls. When cabinet posts were being handed out, Kirkland successfully lobbied for Transport and Communications rather than the expected Social Welfare. She wanted to improve road safety in the province. But the women’s rights issue remained a preoccupation. Later, when the Quebec Civil Code was being debated, she rallied her male party colleagues to support a bill giving married women legal rights. Despite a tough battle through review committees (some men had property listed in their wives’ names for tax purposes), Bill 16 was passed in 1964.

During her 11-year legislative career and three cabinet posts, Kirkland had other weighty responsibilities: she was married to Philippe Casgrain and had three children. When she was first elected, the children were young: Lynne-Marie was 6, Kirkland, 5, and Marc, 1 1/2. She coped by living next door to her mother and hiring a full-time nanny.

“I didn’t feel guilty be-cause I had good help, but it was hard: sometimes I would fly back from Quebec City just to have dinner with the children and leave early the next morning,” she recalled. Daughter Lynne-Marie re-members her mother with some measure of awe. “She was a powerful woman, very organized, a superwoman. She’d come in for dinner on the way to Quebec City or Toronto and spent every weekend with us.” Yet, Lynne-Marie doesn’t think of her mother as ambitious. “It was partly the circumstances. She was urged to run for her father’s riding and once she agreed and won she was responsible. If she says she’s going to do something she does it, by hook or crook.”

For her part, Kirkland sums up the experience: “I worked hard.” Her unhappy marriage ended in divorce and she left politics in 1972 to have a more stable life. In addition to Bill 16, she is equally proud of the establishment of l’Institût d’Hôtelerie on St. Denis street. “I always felt that tourism could develop the wealth of the province,” she says, “and that Quebec’s Latin influence in cooking could be exploited.”

Today, at 73, Marie-Claire Kirkland lives in New Brunswick and Quebec and travels widely with her second husband, Wyndham Strover. He was her law school classmate and friend, but as a divorcé he would have been declared off-limits by her Roman Catholic parents. It was through her yearly McGill fundraising letter that they stayed in touch. The pair married nine years ago.

An astute observer of Quebec politics, she is disturbed by public sector cutbacks and by electoral fraud during the 1995 referendum on Quebec sovereignty. “If I were only 20 years younger, I’d fight.” Few doubt that she’d be a formidable opponent.