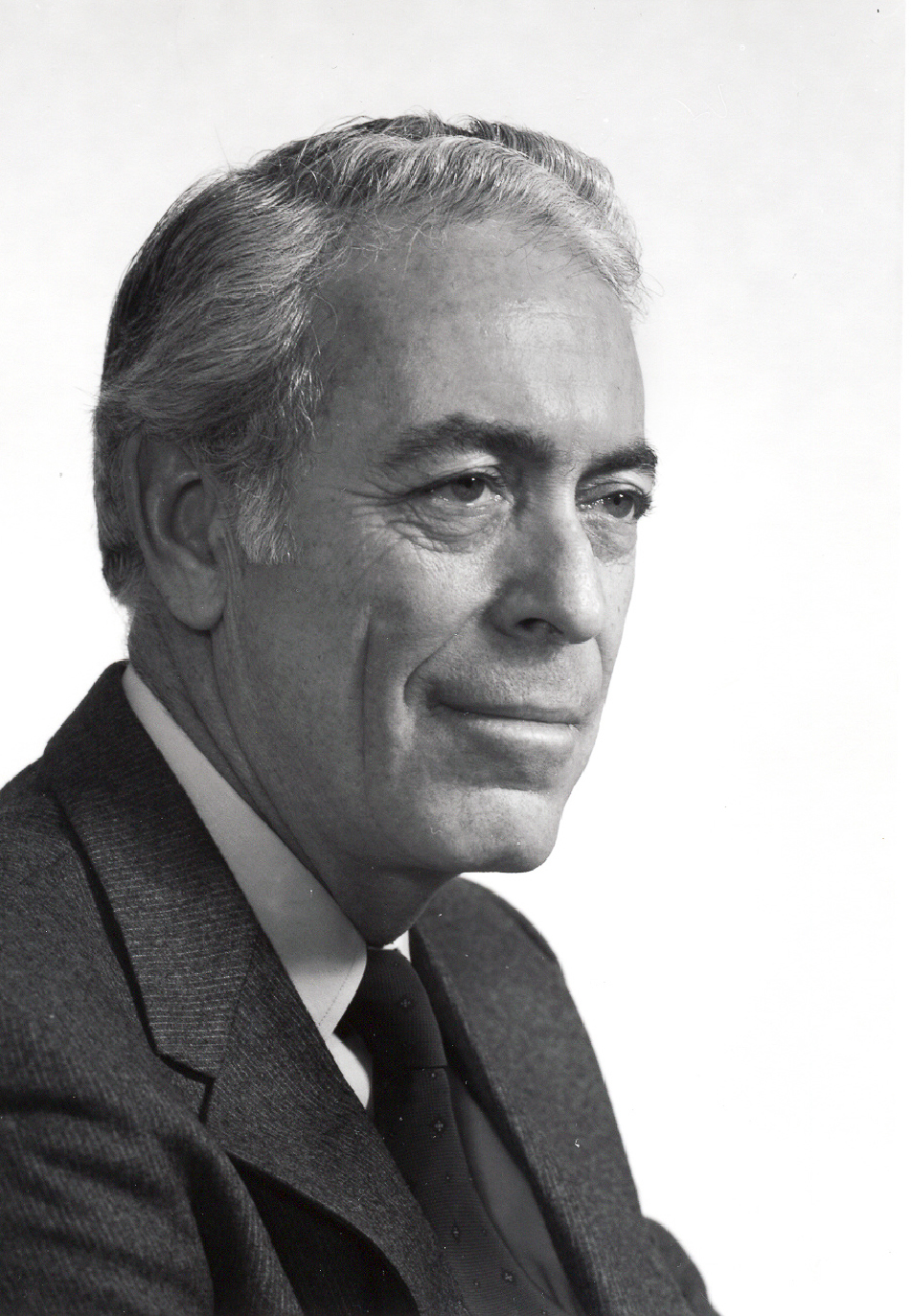

An “unsung hero of Canadian Law” is how then Dean of Law Nicholas Kasirer described Manuel “Manny” Shacter, Ad. E., BCL’47, on the occasion of a special ceremony organized in 2008 to celebrate his career. This year marks another milestone for Manny, as he celebrates his 70th Class Anniversary. We met with him to discuss the highlights of his seven decades in law.

Your face is familiar to many of our readers, as your photo is displayed next to F.R. Scott’s in the hallway of Old Chancellor Day Hall, on a plaque commemorating the Supreme Court case of Brody v. The Queen, 1962.

In the early 1960’s, a censorship case I had, Lady Chatterley’s Lover*, was about to reach the Supreme Court of Canada. I had handled the case through the lower courts, but had never pleaded in front of the Supreme Court. When my client suggested that maybe we should get some counsel, I told him I knew just the guy. I called Professor Frank R. Scott, who had been my Constitutional Law and Obligations professor (he was good enough to pull off such different topics!), and he was delighted to join us on the case. It is then that he wrote the “I went to bat for the Lady Chatte” poem for me. Only Frank R. Scott could get away with a poem like that, that dealt with the problems of the day. At the time, the church still dominated in Quebec.

You studied at the Law Faculty from 1945 to 1947. How was life at the Faculty back then?

We started as a small class of about 14, it dwindled down to ten, and then three more students joined us in 1947. They were returning from service; one student was an admiral, another a general, the third a flight commander. It was impressive to see them walk into class in their uniforms. It was also a time when the law profession was just opening up to women – in our class, there were two and, being such a small group, we were all quite close. Unfortunately, I don’t think they went on to practice.

Also, there were no more than three full-time professors at the Faculty back then – all other courses were given by practicing lawyers coming up from downtown. We had very good instructors. Professor John Peters Humphrey (BCL’29) taught us International Law, and Roman Law, of all things. He was later hired by the nascent United Nations to draft the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, which is now law throughout the world.

You also completed your BA at McGill, so you were a student during the war. Do you have any stories?

One year, someone came to gather people to go west and help with the harvest on the farms, because all the older males were drafted, or had joined the Forces. A group of us from McGill went out there for six weeks—from the end of September to the beginning of November. It was a great learning experience. We moved from farm to farm; some used us, others found us not so good—I can’t blame them! On one farm, the son was a year younger than me; we had a very good rapport—he actually taught me how to drive on a farm truck.

We have Old McGill yearbooks that say you were quite the sportsman.

I was part of the McGill basketball team during my studies. After the war, a friend and I were recruited by the coach of the football team—he wanted guys who could catch, so he approached players at a basketball practice! Later, in 1946 or 1947, I got knocked out while playing, and the McGill Daily reported it in its summary of the game. That day, my Tax Law Lecturer, Claude Richardson of Ogilvy Renault, asked me to stay after class to offer me this advice: “You have to make up your mind. Either you want to be a lawyer, or a football player, but you cannot be both, because of the danger of getting your brains knocked out.” I took his advice and left the football team. Unfortunately, I did not get to thank him once I realized how sound his advice had been, years later when people became much more conscious of concussions.

How did you meet Leo Rosentzveig, with whom you founded the law firm Mendelsohn Rosentzveig Shacter (today McMillan)?

When I graduated, I went to work for the Department of Justice in Ottawa for two years. I got to meet federal judges, cabinet ministers, deputy ministers—people shaping Canada. It was a chance to learn from them. When I decided I wanted to come back to Montreal and practice, I was contacted by a friend of mine, Leo Rosentzveig (BCL’45). He had recently joined Mr. Mendelsohn, an established lawyer. The three of us eventually founded the firm. We had amazing years working together. Leo and I had played on McGill’s basketball team together, we had gone to summer camp as counselors together… Before he died, I wrote him a letter to mention how incredible it was that in all those years, we never had an argument. Leo was notable for strong opinions, but we always found a way to work together.

You have been a trailblazer for the progress of fair representation of Jewish lawyers in the profession. Second Jewish Bâtonnier of Montreal, you were also one of the founders of The Lord Reading Law Society in 1948. How did the Society come to be?

Shortly before my time, the Bar of Quebec announced that its annual convention would be held at Mont Tremblant Lodge. At the time, that venue had posted signs stating, “No Jews Allowed.” The Jewish lawyers decided not to attend the event, and they formed a group that got in touch with the Quebec Bâtonnier. He agreed it was a mistake, but it was too late to change the location. To make sure that it would not happen again, the Jewish lawyers formed The Lord Reading Law Society to advise the Bar on difficult or offensive situations against Jewish jurists.

Shortly before my time, the Bar of Quebec announced that its annual convention would be held at Mont Tremblant Lodge. At the time, that venue had posted signs stating, “No Jews Allowed.” The Jewish lawyers decided not to attend the event, and they formed a group that got in touch with the Quebec Bâtonnier. He agreed it was a mistake, but it was too late to change the location. To make sure that it would not happen again, the Jewish lawyers formed The Lord Reading Law Society to advise the Bar on difficult or offensive situations against Jewish jurists.

Over the years, the Society turned into a lobbying group for Jewish appointments. The very first Jewish judge in Canada was Harry Batshaw (BCL’24), from Montreal. The appointment was well merited on its own, but it was brought to the attention of the Minister that he would be a good judge by The Lord Reading Law Society. His appointment paved the way for Jewish judges to be appointed in other provinces.

We held annual meetings with Justice Ministers. When I was president of The Lord Reading Law Society, the Justice Minister happened to be Pierre Elliot Trudeau. His secretary suggested that we meet on a Sunday. It was strange, but I agreed, and got a few of my executives to come with me. We were waiting for him, dressed in suits and ties, looking like proper lawyers, and surely enough, in walks the Minister of Justice—with a sports jacket, no tie, and sandals, in typical Pierre Elliott Trudeau fashion [laughs]. He was very receptive, and true to his word. His mindset was that he did not care about the religion, persuasion, or sex of the appointee—he only cared about getting good judges.

How has the profession changed in your years of career?

Every year, young lawyers who just graduated say they want to do litigation, or tax law… My advice has always been that for the first two years, you should try to do everything.

Every year, young lawyers who just graduated say they want to do litigation, or tax law… My advice has always been that for the first two years, you should try to do everything.

Then, if you want to specialize, specialize. My feeling is that if you are a lawyer, but you have never been to court, then you don’t really understand an important part of the law.

That being said, in the past, lawyers did not have the luxury to specialize. You took whatever case came through the door. Today, the law has become much more technical, and there is that need for specialization. The Tax Act used to be under 100 pages—not 300 like today.

To this day, you still go to the office. What makes so passionate about law that the flame burns on, 70 years later?

All young law students picture themselves as saving human rights, but you have to face the reality that it does not really happen. That being said, once in a lifetime, you get a case like Lady Chatterley’s Lover, which involves freedom of speech, and truly makes a difference.

I enjoy coming into the office. I hear what’s happening in the legal world, and occasionally someone asks my opinion. Mr. Mendelsohn Senior has died, but his son Max Mendelsohn works at the firm now, and one of Leo Rosentzvieg’s sons is a partner too—the legacy lives on.

* Note from the editor: Lady Chatterley’s Lover is a book by D.H. Lawrence which was confiscated by Quebec authorities as an obscene publication under the Criminal Code, a decision upheld by a trial judge and the Quebec Court of Appeal. The Supreme Court allowed the appeal—on a 5-4 split—, holding that the book did not constitute an obscene publication. The case is still considered a major step forward for human rights in Canada.

Text: Karell Michaud

Photos: Lysanne Larose